The Hangzhou G20 summit – what is at stake?

In

On 4-5 September, the city of Hangzhou is set to host the first ever summit of G20 leaders in China. By welcoming G20 leaders for their 11th gathering, China is hitting another crucial milestone in demonstrating its increasing indispensability to global economic governance, following the organisation of the 2014 summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and a successful push for adding the renminbi to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) currency basket last year

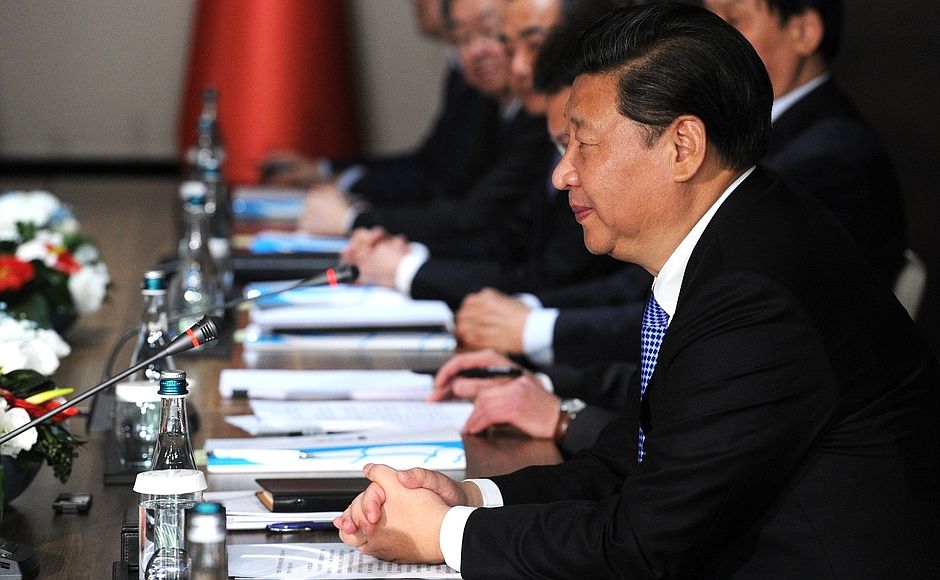

(Photo credit: motiqua, Flickr)

*****

The Hangzhou G20 summit – what is at stake?

On 4-5 September, the city of Hangzhou is set to host the first ever summit of G20 leaders in China. By welcoming G20 leaders for their 11th gathering, China is hitting another crucial milestone in demonstrating its increasing indispensability to global economic governance, following the organisation of the 2014 summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and a successful push for adding the renminbi to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) currency basket last year.

The Communist Party of China (CPC) officially announced its priorities on 1 December 2015 for the coming summit, which will also be attended by several guests including Kazakhstan, Laos and Egypt. Building on the three Is (Inclusiveness, Implementation and Investment) of the 2015 Antalya meeting, China has also structured its priorities around ‘I words’: “Towards an Innovative, Invigorated, Interconnected and Inclusive world economy.” Paradoxically however, while China will seek G20 members’ assent to formulating joint action plans necessary to further the above objectives, international progress on these issues is, in fact, often impeded by the CPC’s inability to enact changes on the domestic front.

By putting innovation as the foremost priority on the G20’s agenda, China seeks to ensure that growth across G20 countries is increasingly led by innovation. It is also not by accident that the CPC has chosen Zheijang province to host the gathering – a region that is the source of some of China’s most innovative companies such as Alibaba and Geely. While rendering domestic environments more conducive to innovation hinges on local legislation, the G20 in Hangzhou may serve to co-ordinate national efforts and share best practices, potentially also resulting in a blueprint for innovation-led growth. China may also initiate the review of the 2014 Brisbane summit’s commitment to lift the G20’s collective GDP by at least an additional two percent above current trajectories, so as to ensure that growth strategies are innovation-centred. However, given that innovation policies tend to yield results in the long term (contrasting with the G20’s focus hitherto on immediate crisis management), a key challenge for the major economies will reside in striking a balance with expedient policy options.

The objective of creating an invigorated economy is the CPC’s response to the increasingly fragmented flow of goods and services across borders. While regional trade agreements do facilitate commerce among the countries they cover, they also hamper the optimal allocation of key factors of production at the global level through the diversions they often cause. For Beijing, a reinvigorated world economy must also go in hand with the reform of international trade, investment and finance regimes. Despite improvements in China’s and other emerging powers’ representation in key organs of global governance (IMF, World Bank, Financial Stability Board, Basel Committee), trade liberalisation has essentially shifted from the multilateral track to the regional level (often in a competitive manner), risking to bring about a structural slow-down in the global economy.

The fact remains that China’s interests continue to be best served by trade liberalisation through the World Trade Organisation (WTO) for at least two reasons. First, China’s trade-to-GDP ratio remains almost double that of the US. Second, China’s trade still consists primarily of merchandise exports rather than high-end services associated with developed countries. Because of the fact that the regulation of services are more likely to escape WTO expansion than that of merchandise, China has secured immense relative gains from multilateral trade liberalisation. At a moment when trade negotiations proceed mainly through mega-regional trade and investment agreements promulgated mainly by the United States through the – stalled – Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the already concluded (but not ratified) Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), China has been using its G20 presidency to try and push trade talks back to the multilateral level. Amongst the several geopolitical consequences of the United States writing the rules of trade in East and Southeast Asia are the reduced dependence of regional countries on Chinese trade and the resulting internal and external pressure on China to liberalise its economy. While Beijing’s approach towards the TPP has been gradually shifting from disdain to cautious embrace, the political and economic costs of China joining the TPP remain substantial. It is therefore no accident that the CPC retains a preference for treating trade as a global rather than regional issue – even if China does negotiate regional trade agreements with Japan, South Korea and a handful of other nations in Asia and Oceania through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Beijing’s efforts to place trade firmly on the G20’s agenda already led to the formation of the Trade & Investment G20 Working Group early this year, followed by the organisation of the first ever G20 Trade Ministerial last July in Shanghai. This latter resulted in the adoption of joint broad principles for stimulating trade and guiding investment policy making.

Despite Beijing’s efforts to push for a coherent approach to investment liberalisation, the Chinese market remains difficult to access for foreign investors, notably in sectors such as petrochemicals, energy and telecommunications. In addition, China is also hindering negotiations on various plurilateral trade agreements negotiated outside the remit of the WTO. As a participant in the talks on the Environmental Goods Agreement (that aims to remove barriers to trade in green goods), Beijing has so far opposed significant tariff reductions. In addition, the country has also failed to comply with the 1 July deadline to implement the first set of tariff cuts entailed by the expanded Information Technology Agreement rubberstamped at the WTO ministerial in Nairobi last December. Another contentious issue on the G20’s agenda will concern industrial overcapacities (notably in the steel sector) which China will likely attempt to present as a global rather than Chinese issue. In spite of continuous domestic action, China continues to face numerous anti-dumping procedures by reason of its underpriced steel export – particularly from the United States and Europe.

China will likely also use the Hangzhou summit to urge the launch of the 15th quota review process within the IMF, delayed by years due to the late adoption of 2010 reforms by the US Congress. According to data published by the IMF in July 2015, an additional 6.2 percentage points of shift in quota shares from advanced to emerging market economies would be necessary to reflect current economic reality. Nevertheless, any reforms that could result in China overtaking Japan in terms of governance influence or the United States loosing its veto power will be politically difficult if not impossible to push through local legislation in Tokyo and Washington. Consequently, the emphasis may rather shift towards the review of the quota formula by boosting, for example, the weight of purchasing power parity considerations to the detriment of current market exchange rates. But while China is pushing for the reform of international financial institutions, it struggles to overhaul its own domestic market institutions, which have seen a considerable part of their influence shift towards the ruling party since President Xi Jinping’s arrival into power in November 2012. The resulting competition for the remnant of influence is most obvious between Ministry of Commerce and the People’s Bank, on the one hand, and the Ministry of Finance on the other, which have battled for years over how much fiscal space China has to spend.

The interconnectivity aspect reflects China’s approach to development policy. It builds on Beijing’s recent successes in realising rapid growth by focusing on physical infrastructure development as a motor of sustained economic growth. China has mobilised significant efforts to take on a more active role in international development policy, including through the Belt & Road initiative that seeks to boost on- and offshore linkages between Europe and China by investing into – among others – infrastructure projects in Central and South Asia. A closely pertinent initiative is the presently 46-strong Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) that, together with $40 billion Silk Road Fund, is intended to finance the projects carried out under the B&R. The Hangzhou meeting will represent an opportunity for China to build on and further the achievements of the 2013 St. Petersburg G20 summit that saw the creation of the Investment & Infrastructure Working Group and the 2014 Brisbane summit that gave rise to the Global Infrastructure Hub with the aim of harmonising approaches to infrastructure building. China and other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) may also seize the occasion to demonstrate their preparedness to build bridges between the recently created multilateral development banks (such as the New Development Bank and the AIIB) on the one hand, and the traditional financial institutions on the other.

Finally, the inclusive growth component appears to indicate China’s determination to build a harmonious relationship in the domestic context between economic growth, society and the environment. Responding to growing regional inequalities, widening income gaps and worsening environmental degradation, the objective of realising inclusive growth has also been enshrined into the 13th five year plan (2016-2020). This year’s G20 meeting is an occasion for China to push members to formulate concrete plans to implement the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and monitor the implementation of the Multi-Year Development Action Plan approved at the 2010 G20 in Seoul.

In brief, while China’s presidency has already had its transformative impact on the G20 process (notably through the championing of trade), the key moment for Beijing to demonstrate its readiness for international leadership – backed up with decisive domestic action – in economic governance will come in the form of the Hangzhou summit – the world will be watching.